Using AI to find heterogeneous scientific speakers

(Alt title: how I am using AI to prevent manels and how you can too)

So I am currently in the process of organizing a seminar series in biomedical engineering and also a conference on artificial intelligence in molecular biology. As part of both of these efforts, I (and my co-organizers) need to recruit speakers.

Ideally, we would like speakers to be heterogeneous, spanning a diverse array of topics and subdisciplines related to the event, but also representing diverse institutions, diverse gender and ethnic backgrounds, with perhaps even a good amount of industry and international representation especially in the conference setting. We believe this kind of heterogeneous representation of speakers would give the audience a broader range of perspectives and ultimately make for a more interesting event.

However, I have found finding heterogeneous speakers to be quite challenging! Having been at Harvard for most of my academic training means most people in my network are in that area. So when I am asked to think of possible speakers, the people who first come to mind are often unsurprisngly the folks I know from the Harvard area! Likewise, I have been and am still in the rather male-dominated field of bioinformatics. As such, most friends and colleagues I am surrounded by have been and continue to be men. So when I try to come up with a list of a limited number of speakers, it is quite easy for me to accidentally come up with a manel (all-male panel) of speakers simply because I know so many men.

It’s taking quite a lot of time and effort to scower social media, read papers and cross reference lab websites, etc, all to find potentially more heterogenous speakers. There must be a better way!

In the rest of this blog post, I will show I used AI (really it’s just automation with web scraping and database referencing but it’s cooler to call it AI these days) to augment my intelligence and help identify potential heterogeneous speakers!

(Disclosure: I will be using Claude.ai to help me write some code. I have proof-read and tweaked the code but did not write it from scratch so I am sure there are inefficiencies and weird algorithmic/coding choices that I would’ve not have implemented if done from scratch. But I did find it very helpful (for example for identifying weird HTML tags for web scraping that I otherwise would’ve had to spend a lot of time identifying) and it saved me quite a lot of time simply typing. So…thanks AI (thumbs up).)

Step 1: Finding the experts using Google Scholar

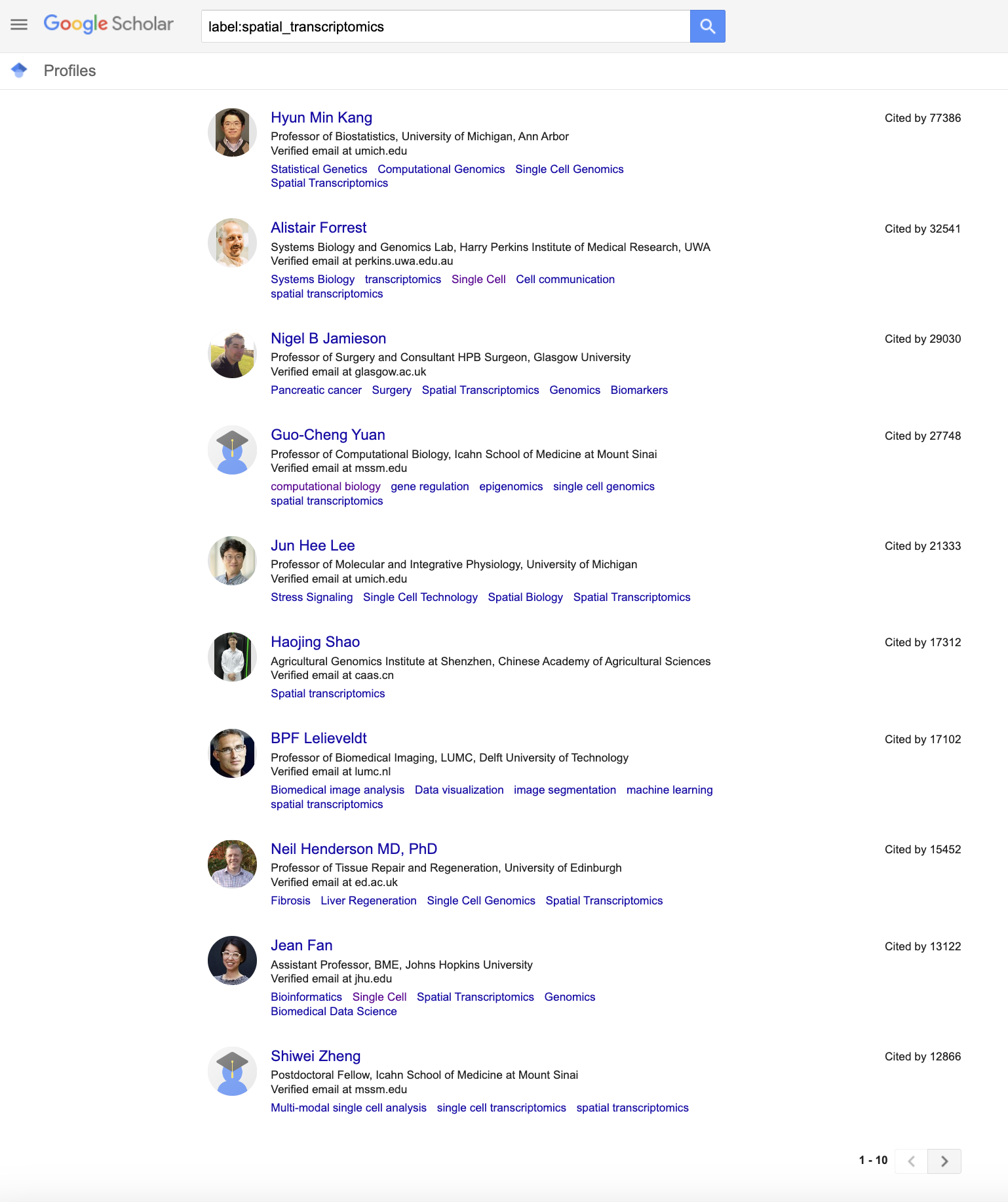

Even when I am manually trying to find potential heterogeneous speakers, my first go-to is Google Scholar. I can browse by subject labels and see who are the experts in that field. Let’s look at my niche subfield of spatial transcriptomics as an example.

Typically, I would just manually go through these Google Scholar results, focusing on women speakers for example in my effort to avoid a manel. However, while this may help me avoid a manel, it may not lead to a heterogeneous speaker panel. Heterogeneity is a property of a group, not any individual. So if I simply noted all the women, I could end up with an all-women panel, which is also not very heterogeneous. So this creates a challenge in that I first need to identify all possible speakers and then iteratively narrow it down to (say) 5 who are collectively heterogeneous based on some set of features such as institution, gender, race, etc. Very time consuming!

Let’s scrape Google Scholar to first get the information for all these potential speakers. I will have Claude.ai assist me and have included my prompts so you can try them out for yourself.

Jean: You are using R to scrape content from Google Scholar. You want to search for a specific label such as spatial transcriptomics via https://scholar.google.com/citations? view_op=search_authorshl=en&mauthors=label:spatial_transcriptomics You will then scrap the name, institution, and cited by information and organize the results in a data frame.

(I’ve modified the output code slightly and have annotated where I made the modifications)

library(rvest)

library(dplyr)

# Function to scrape Google Scholar authors

scrape_google_scholar <- function(label, max_pages = 10) {

# Jean: clean up input

label = gsub(' ', '_', label)

base_url <- "https://scholar.google.com/citations"

results <- data.frame()

next_token <- ""

page <- 1

while(page <= max_pages) {

# Construct URL with proper pagination

if(next_token == "") {

url <- sprintf(

"%s?view_op=search_authors&hl=en&mauthors=label:%s",

base_url,

label

)

} else {

url <- sprintf(

"%s?view_op=search_authors&hl=en&mauthors=label:%s&after_author=%s&astart=%d",

base_url,

label,

next_token,

(page - 1) * 10

)

}

# Jean: add delay; please don't ban me Google

Sys.sleep(3)

tryCatch({

# Read the page

page_html <- read_html(url)

# Extract author names

names <- page_html %>%

html_nodes(".gs_ai_name a") %>%

html_text()

# Extract institutions

institutions <- page_html %>%

html_nodes(".gs_ai_aff") %>%

html_text()

# Extract citation counts

citations <- page_html %>%

html_nodes(".gs_ai_cby") %>%

html_text() %>%

gsub("Cited by ", "", .) %>%

as.numeric()

# Extract author IDs for pagination

author_links <- page_html %>%

html_nodes(".gs_ai_name a") %>%

html_attr("href")

# Extract next page token

next_button <- page_html %>%

html_nodes(".gs_btnPR") %>%

html_attr("onclick")

if(length(next_button) > 0) {

# Extract the after_author parameter from the encoded URL string

# First decode the URL-encoded string

decoded_url <- gsub("\\\\x26", "&", gsub("\\\\x3d", "=", next_button))

# Then extract the after_author parameter

next_token <- regmatches(

decoded_url,

regexpr("after_author=[^&]*", decoded_url)

)

next_token <- gsub("after_author=", "", next_token)

} else {

# No next button found, we've reached the end

next_token <- NULL

}

# Create temporary dataframe for this page

page_df <- data.frame(

Author = names,

Institution = institutions,

Citations = citations,

AuthorID = gsub("/citations\\?.*user=(.*)&.*", "\\1", author_links),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)

# Append to results

results <- rbind(results, page_df)

# Break if no next token or no results on current page

if(is.null(next_token) || length(names) == 0) {

message(sprintf("Reached end of results at page %d", page))

break

}

page <- page + 1

}, error = function(e) {

message(sprintf("Error on page %d: %s", page, e$message))

return(NULL)

})

}

return(results)

}

# Example usage

label <- "spatial transcriptomics"

authors_data <- scrape_google_scholar(label, max_pages = 5)

head(authors_data, n=10)

Author Institution Citations AuthorID

1 Hyun Min Kang Professor of Biostatistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 77386 /citations?hl=en&user=8e0jy0IAAAAJ

2 Alistair Forrest Systems Biology and Genomics Lab, Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, UWA 32541 /citations?hl=en&user=lxBtOAoAAAAJ

3 Nigel B Jamieson Professor of Surgery and Consultant HPB Surgeon, Glasgow University 29030 /citations?hl=en&user=YH9VWWoAAAAJ

4 Guo-Cheng Yuan Professor of Computational Biology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 27748 /citations?hl=en&user=1s6ZkyQAAAAJ

5 Jun Hee Lee Professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan 21333 /citations?hl=en&user=jdz0zcsAAAAJ

6 Haojing Shao Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences 17312 /citations?hl=en&user=qAaKmKsAAAAJ

7 BPF Lelieveldt Professor of Biomedical Imaging, LUMC, Delft University of Technology 17102 /citations?hl=en&user=J20kK1oAAAAJ

8 Neil Henderson MD, PhD Professor of Tissue Repair and Regeneration, University of Edinburgh 15452 /citations?hl=en&user=586JfA4AAAAJ

9 Jean Fan Assistant Professor, BME, Johns Hopkins University 13122 /citations?hl=en&user=EEX1uGwAAAAJ

10 Shiwei Zheng Postdoctoral Fellow, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 12866 /citations?hl=en&user=Pwu1X7cAAAAJ

Great! So this provided us with the author’s names, Institutions, and number of citations. I could use the number of citations to filter for the most well-cited authors for a keynote speaker if I wanted to. I also have their author IDs available if I want to look at their Google Scholar profiles and read up on their recent papers.

As I scarped only 5 pages, with 10 scholars per page, this gives us a set of 50 scholars from which I can pick 5 potential speakers.

Step 2: Annotate speaker features

So now I want to optimize heterogeneity among a subset of 5 potential speakers along certain categorical features of interest such as institution, gender, and race. Institutional information is also provided by Google Scholar, though admittedly these are not the most clean because they are provided by each scholar. So some times, a scholar notes their institution as Harvard/Broad, some times it’s just Broad, some times it’s Harvard Medical School / Broad Institute, some times it’s the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. You get the idea; there are many strings that correspond to the same institution. If someone is able to find an algorithm to automatically clean up these institution names and perhaps even annotate by continent, please do let me know!

But for now, let’s focus on getting each person’s gender and race information. Note this information is not provided through Google Scholar. But we could try to infer each person’s gender and race by cross referencing annotated with gender and race information in the US Census and Social Security Administration database or other databases for example. If a person is named ‘Peter’ and 99% of entries annotated in the US Census and Social Security Administration database with the first name ‘Peter’ is male, then we have a pretty good guess the person is male. This is of course not a full-proof approach. But it is a high-throughput approach to help us annotate potentially hundreds of names.

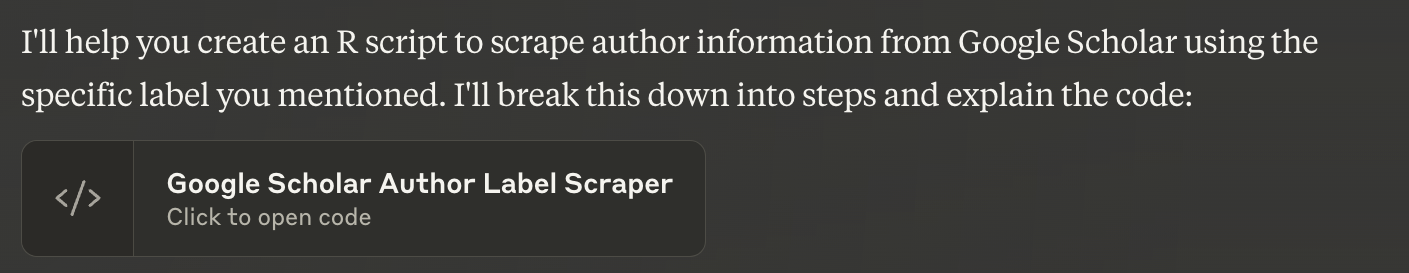

I asked Claude.ai to help me with such a prediction but it wouldn’t do it!

Jean: You are coding in R. Given a name like ‘Peter’, reference the US census or other databases to form a probabilistic prediction of the person’s gender and race/ethnic background.

So I had to code it up myself. Luckily it looks like someone already made a handy R package to do exactly this!

I did ask Claude.ai to help me parse out the first and last names though.

Jean: Given a list of names, which may include something like the following, extract out the first names as a vector called firstname and the surnames as a vector called lastname

[1] “Hyun Min Kang” “Alistair Forrest”

[3] “Nigel B Jamieson” “Guo-Cheng Yuan”

[5] “Jun Hee Lee” “Haojing Shao”

[7] “BPF Lelieveldt” “Neil Henderson MD, PhD”

# Function to parse names into first and last name components

parse_names <- function(names) {

# Remove titles and degrees

names <- gsub("MD|PhD|Dr\\.|Prof\\.", "", names)

names <- trimws(names) # Remove extra whitespace

# Initialize vectors

firstname <- character(length(names))

lastname <- character(length(names))

for (i in seq_along(names)) {

# Split name into parts

parts <- strsplit(names[i], "\\s+")[[1]]

if (length(parts) == 1) {

# Single name

firstname[i] <- parts[1]

lastname[i] <- NA

} else if (length(parts) == 2) {

# Standard "First Last" format

firstname[i] <- parts[1]

lastname[i] <- parts[2]

} else if (length(parts) == 3) {

# Handle cases like "First Middle Last" or "First B Last"

if (nchar(parts[2]) == 1 || grepl("^[A-Z]\\.$", parts[2])) {

# If middle part is initial

firstname[i] <- parts[1]

lastname[i] <- parts[3]

} else if (grepl("^[A-Z][a-z]+$", parts[1]) && grepl("^[A-Z][a-z]+$", parts[2])) {

# If first two parts look like a double first name

firstname[i] <- paste(parts[1], parts[2])

lastname[i] <- parts[3]

} else {

# Default to first part as first name, rest as last name

firstname[i] <- parts[1]

lastname[i] <- paste(parts[2:length(parts)], collapse = " ")

}

} else {

# For longer names, take first part as first name and rest as last name

firstname[i] <- parts[1]

lastname[i] <- paste(parts[2:length(parts)], collapse = " ")

}

}

return(list(firstname = firstname, lastname = lastname))

}

names <- parse_names(authors_data$Author)

I then combined Claude.ai’s name parser with what I learned from the predictrace tutorials to annotate each scholar in the previous results data frame with the most likely predicted gender and race information.

# Jean's code

library(predictrace)

gender <- predict_gender(names$firstname)

race <- predict_race(names$lastname, surname = TRUE)

results <- cbind(authors_data, gender = gender$likely_gender, race = race$likely_race)

head(results, n=10)

Author Institution Citations

1 Hyun Min Kang Professor of Biostatistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 77386

2 Alistair Forrest Systems Biology and Genomics Lab, Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, UWA 32541

3 Nigel B Jamieson Professor of Surgery and Consultant HPB Surgeon, Glasgow University 29030

4 Guo-Cheng Yuan Professor of Computational Biology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 27748

5 Jun Hee Lee Professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan 21333

6 Haojing Shao Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences 17312

7 BPF Lelieveldt Professor of Biomedical Imaging, LUMC, Delft University of Technology 17102

8 Neil Henderson MD, PhD Professor of Tissue Repair and Regeneration, University of Edinburgh 15452

9 Jean Fan Assistant Professor, BME, Johns Hopkins University 13122

10 Shiwei Zheng Postdoctoral Fellow, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 12866

AuthorID gender race

1 /citations?hl=en&user=8e0jy0IAAAAJ <NA> asian

2 /citations?hl=en&user=lxBtOAoAAAAJ male white

3 /citations?hl=en&user=YH9VWWoAAAAJ male white

4 /citations?hl=en&user=1s6ZkyQAAAAJ <NA> asian

5 /citations?hl=en&user=jdz0zcsAAAAJ male asian

6 /citations?hl=en&user=qAaKmKsAAAAJ <NA> asian

7 /citations?hl=en&user=J20kK1oAAAAJ <NA> <NA>

8 /citations?hl=en&user=586JfA4AAAAJ <NA> <NA>

9 /citations?hl=en&user=EEX1uGwAAAAJ female asian

10 /citations?hl=en&user=Pwu1X7cAAAAJ <NA> asian

Step 3: Maximize entropy among subset

Now, given these 50 scholars and their institution, gender, and race annotations, let’s see if we can narrow down to 5 heterogeneous speakers. I will use the mathematical principles of information entropy to achieve this. The goal will be to iteratively consider groups of 5 scholars with the most difference in terms of their institution, race, and gender annotations ie. maximizing entropy.

I will again ask Claude.ai for some coding help. I will change up the language so it doesn’t block me from doing things related to gender and race though.

Jean: You are coding in R. You have a data frame where each row is an item. You have two columns corresponding to two categorical features associated with each item: color and shape. You have 100 items. You want to subset to 10 items that are the most diverse in terms of their collective color and shape. Use entropy to help achieve this.

# Function to calculate entropy of a categorical vector

calculate_entropy <- function(x) {

# Get probability distribution

prob_dist <- table(x) / length(x)

# Calculate entropy: -sum(p * log(p))

-sum(prob_dist * log(prob_dist))

}

# Function to calculate combined entropy for multiple categorical variables

calculate_combined_entropy <- function(df, columns) {

# Sum the entropy of each column

sum(sapply(df[columns], calculate_entropy))

}

# Function to find diverse subset using entropy

find_diverse_subset <- function(df, feature_cols, subset_size, max_iterations = 1000) {

n <- nrow(df)

best_entropy <- -Inf

best_subset <- NULL

# Run multiple iterations with random starting points

for(i in 1:max_iterations) {

# Start with random subset

current_indices <- sample(1:n, subset_size)

current_subset <- df[current_indices, ]

current_entropy <- calculate_combined_entropy(current_subset, feature_cols)

# Try to improve the subset

improved <- TRUE

while(improved) {

improved <- FALSE

# For each item in the subset

for(j in 1:subset_size) {

# Try replacing it with each item not in the subset

other_indices <- setdiff(1:n, current_indices)

for(new_idx in other_indices) {

# Create temporary subset with the replacement

temp_indices <- current_indices

temp_indices[j] <- new_idx

temp_subset <- df[temp_indices, ]

temp_entropy <- calculate_combined_entropy(temp_subset, feature_cols)

# If this improves entropy, keep the change

if(temp_entropy > current_entropy) {

current_indices <- temp_indices

current_entropy <- temp_entropy

improved <- TRUE

break

}

}

if(improved) break

}

}

# Update best result if this iteration found a better solution

if(current_entropy > best_entropy) {

best_entropy <- current_entropy

best_subset <- current_indices

}

}

return(list(

subset = df[best_subset, ],

indices = best_subset,

entropy = best_entropy

))

}

Note the algorithm here: we are grabbing 5 scholars, checking their entropy, and if the entropy is increased compared to the previous 5 scholars, we will save the new 5 scholars, and repeat this 1000 times. I’m sure there are way way more efficient algorithms so if you have suggestions, please feel free to let me know.

# Example usage:

set.seed(1) # For reproducibility

# Find diverse subset

final <- find_diverse_subset(

df = results,

feature_cols = c("Institution", "gender", "race"), # Jean: change to features we want

subset_size = 5

)

# Print results

print(final$subset)

print(paste("Combined entropy:", round(final$entropy, 3)))

Author Institution Citations

9 Jean Fan Assistant Professor, BME, Johns Hopkins University 13122

15 Catia Moutinho CEO at The Single-Cell World 8059

1 Hyun Min Kang Professor of Biostatistics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 77386

34 Can Altunbulakli Post-Doctoral Researcher, Lund University 3165

23 Roy Wollman Professor of Integrative Biology and Physiology and Chemistry and Biochemistry, University 4869

AuthorID gender race

9 /citations?hl=en&user=EEX1uGwAAAAJ female asian

15 /citations?hl=en&user=cff0gw8AAAAJ female white

1 /citations?hl=en&user=8e0jy0IAAAAJ <NA> asian

34 /citations?hl=en&user=-NPvXuYAAAAJ male <NA>

23 /citations?hl=en&user=KxC7KRwAAAAJ male white

Combined entropy: 3.076

But in the end, we have our 5 speakers (me being included is purely by chance haha)! I actually don’t personally know any of these folks (yet) so this is definitely a list of 5 that I wouldn’t have been able to come up with on my own! I did manually pull their pictures just for curiosity ;)

Step 5: Double check results

In a real-world setting, I would double check by seeing if these speakers are still active in this area of research by looking at their latest papers. Some events like our seminar series cannot accomodate international speakers due to budgetary limits, so that may lead me to exclude a few speakers. I may also want a good representative of junior and senior scientists depending on the event, so I may manually double check if my final set of 5 has good representation of diverse career stages.

Of course, the gender and race prediction algorithm itself is prone to error, particularly for names that may be under-represented in the US. Beyond the incorrect gender and race inferences, there are also many missing value ie. NAs for genders and races could not be inferred from a name. Even institutions noted may be incorrect because people can change institutions and move. People also retire or passed on. So it’s definitely worth double checking!

But checking up on a handful of speakers is still much easier than potentially looking through 100s because AI has helped us narrow things down!

Conclusions

Of course, there are many limitations to this approach. Beyond the gender and race prediction issues noted previously, there are biases imposed by Google Scholar itself that may prevent us from including certain people who, for example, do not have Google Scholar profiles.

Further, our current approach scrapes through only the first n pages of Google Scholar results, which is sorted by citation count. Citation count has been shown to exhibit gender and racial biases, suggesting that we may need to parse through more pages to find more women and black scholars for example.

And there are other aspects of heterogeneity that may not be easily inferred in this automated manner such as disability status, socio-economic background, immigration status, etc, that could also be worth considering.

But overall, I hope this helps give students a sense of how to use AI to creatively augment our own capabilities and how we can intentionally use AI to help mitigate our own biases and work towards equity and inclusion.

Try it out for yourself!

- Download all the code in one R script

- What happens when you use this approach to make a speaker panel for your field?

- Instead of Google Scholar, what about repeating this with SemanticScholar.org?

Recent Posts

- RNA velocity in situ infers gene expression dynamics using spatial transcriptomics data on 13 October 2025

- Analyzing ICE Arrest Data - Part 2 on 27 September 2025

- Analyzing ICE Detention Data from 2021 to 2025 on 10 July 2025

- Multi-sample Integrative Analysis of Spatial Transcriptomics Data using Sketching and Harmony in Seurat on 22 April 2025

- Using AI to find heterogeneous scientific speakers on 04 November 2024