Identifying And Characterizing Heterogeneity In Single Cell Rnaseq Data

Identifying and Characterizing Heterogeneity in Single Cell RNA-seq Data

In this tutorial, we will become familiar with a few computational techniques we can use to identify and characterize heterogeneity in single cell RNA-seq data. Pre-prepared data for this tutorial can be found as part of the Single Cell Genomics 2016 Workshop I did at Harvard Medical School.

Getting started

A single cell dataset from Camp et al. has been pre-prepared for you. The data is provided as a matrix of gene counts, where each column corresponds to a cell and each row a gene.

load('../../data/cd.RData')

# how many genes? how many cells?

dim(cd)

## [1] 23228 224

# look at snippet of data

cd[1:5,1:5]

## SRR2967608 SRR2967609 SRR2967610 SRR2967611 SRR2967612

## 1/2-SBSRNA4 1 18 0 0 0

## A1BG 0 0 2 0 0

## A1BG-AS1 0 0 0 0 0

## A1CF 0 0 0 0 0

## A2LD1 0 0 0 0 0

# filter out low-gene cells (often empty wells)

cd <- cd[, colSums(cd>0)>1.8e3]

# remove genes that don't have many reads

cd <- cd[rowSums(cd)>10, ]

# remove genes that are not seen in a sufficient number of cells

cd <- cd[rowSums(cd>0)>5, ]

# how many genes and cells after filtering?

dim(cd)

## [1] 12453 224

# transform to make more data normal

mat <- log10(as.matrix(cd)+1)

# look at snippet of data

mat[1:5, 1:5]

## SRR2967608 SRR2967609 SRR2967610 SRR2967611 SRR2967612

## 1/2-SBSRNA4 0.3010300 1.278754 0.0000000 0 0.000000

## A1BG 0.0000000 0.000000 0.4771213 0 0.000000

## A2M 0.0000000 0.000000 0.0000000 0 0.000000

## A2MP1 0.0000000 0.000000 0.0000000 0 0.000000

## AAAS 0.4771213 1.959041 0.0000000 0 1.361728

In the original publication, the authors proposed two main subpopulations: neurons and neuroprogenitor cells (NPCs). These labels have also been provided to you as a reference so we can see how different methods perform in recapitulating these labels.

load('../../data/sg.RData')

head(sg, 5)

## SRR2967608 SRR2967609 SRR2967610 SRR2967611 SRR2967612

## neuron neuron neuron npc neuron

## Levels: neuron npc

PCA

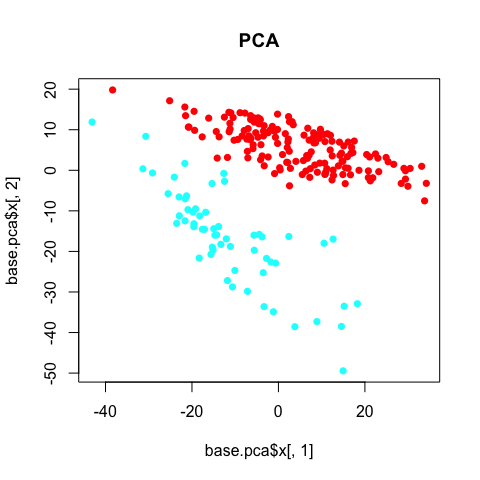

Note that there are over 10,000 genes that can be used to cluster cells into subpopulations. One common technique to identify subpopulations is by using dimensionality reduction to summarize the data into 2 dimensions and then visually identify obvious clusters. Principal component analysis (PCA) is a linear dimensionality reduction method.

# use principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction

base.pca <- prcomp(t(mat))

# visualize in 2D the first two principal components and color by cell type

plot(base.pca$x[,1], base.pca$x[,2], col=rainbow(2)[sg], pch=16, main='PCA')

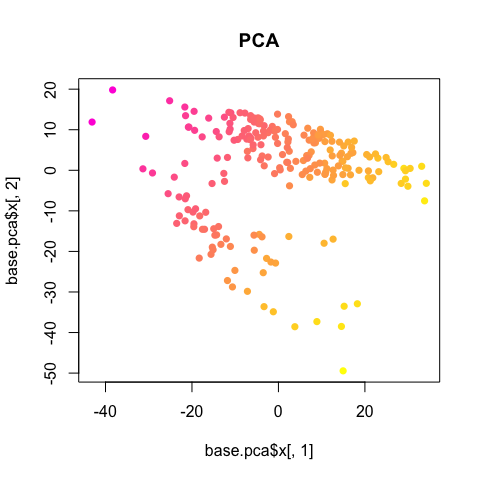

The PCA clearly separates the two annotated subpopulations. However, we can see some additional aspects of heterogeneity driving the first principal componenent. Coloring each cell by its library size reveals that this first component is being driven by variation in library size, which, in this case, can be interpreted as technical noise as opposed to biological insight.

lib.size <- colSums(mat)

plot(base.pca$x[,1], base.pca$x[,2], col=colorRampPalette(c("magenta", "yellow"))(100)[round(lib.size/max(lib.size)*100)], pch=16, main='PCA')

So we should always double check for obvious, non-biological factors (such as library size, batch, patient/mouse, etc), potentially influencing or driving observed heterogeneity.

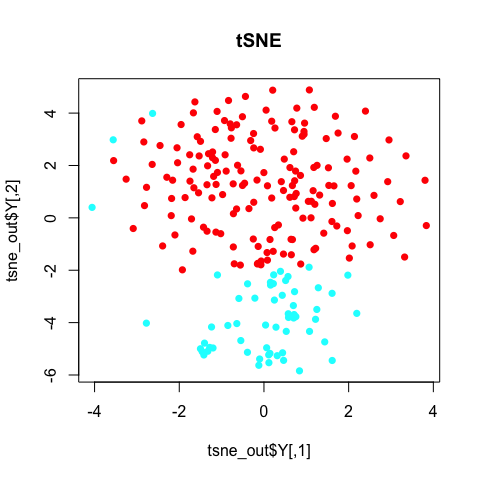

tSNE

T-embedded stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) is a non-linear dimensionality reduction method. Note that in tSNE, the perplexity parameter is an estimate of the number of effective neighbors. Here, we have 224 cells. A perplexity of 10 is suitable. For larger or smaller numbers of cells, you will want to change the perplexity accordingly.

library(Rtsne)

d <- dist(t(mat))

set.seed(0) # tsne has some stochastic steps (gradient descent) so need to set random

tsne_out <- Rtsne(d, is_distance=TRUE, perplexity=10, verbose = TRUE)

## Read the 224 x 224 data matrix successfully!

## Using no_dims = 2, perplexity = 10.000000, and theta = 0.500000

## Computing input similarities...

## Building tree...

## - point 0 of 224

## Done in 0.01 seconds (sparsity = 0.243025)!

## Learning embedding...

## Iteration 50: error is 118.973680 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 100: error is 127.558911 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 150: error is 123.943221 (50 iterations in 0.07 seconds)

## Iteration 200: error is 130.050267 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 250: error is 127.913196 (50 iterations in 0.08 seconds)

## Iteration 300: error is 3.617403 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 350: error is 2.286202 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 400: error is 2.190548 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 450: error is 2.133582 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 500: error is 2.086473 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 550: error is 2.060643 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 600: error is 2.031325 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 650: error is 1.983069 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 700: error is 1.846377 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 750: error is 1.827168 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 800: error is 1.825835 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 850: error is 1.825061 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 900: error is 1.825387 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 950: error is 1.824545 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 1000: error is 1.823723 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Fitting performed in 0.98 seconds.

plot(tsne_out$Y, col=rainbow(2)[sg], pch=16, main='tSNE')

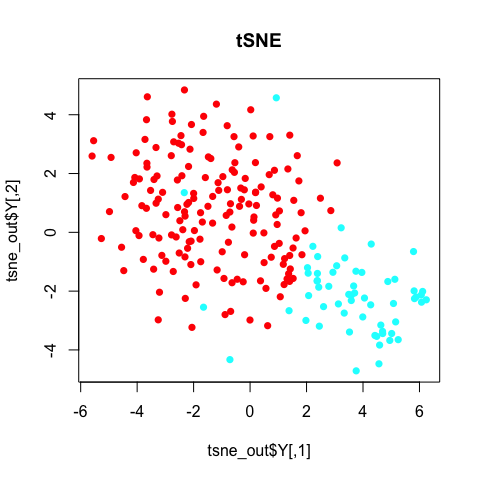

Note with tSNE, your results are stochastic. Change the random seed, change your results. (If you don’t use a random seed at all, your results will be different every time! So always use a random seed to ensure reproducable research!)

set.seed(1) # tsne has some stochastic steps (gradient descent) so need to set random

tsne_out <- Rtsne(d, is_distance=TRUE, perplexity=10, verbose = TRUE)

## Read the 224 x 224 data matrix successfully!

## Using no_dims = 2, perplexity = 10.000000, and theta = 0.500000

## Computing input similarities...

## Building tree...

## - point 0 of 224

## Done in 0.01 seconds (sparsity = 0.243025)!

## Learning embedding...

## Iteration 50: error is 123.486260 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 100: error is 127.644744 (50 iterations in 0.07 seconds)

## Iteration 150: error is 125.135074 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 200: error is 129.868562 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 250: error is 138.279847 (50 iterations in 0.06 seconds)

## Iteration 300: error is 4.395593 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 350: error is 3.569927 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 400: error is 2.725121 (50 iterations in 0.05 seconds)

## Iteration 450: error is 2.243356 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 500: error is 2.204841 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 550: error is 2.168027 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 600: error is 2.136227 (50 iterations in 0.03 seconds)

## Iteration 650: error is 2.094058 (50 iterations in 0.03 seconds)

## Iteration 700: error is 2.045998 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 750: error is 2.039275 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 800: error is 2.028664 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 850: error is 2.007481 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Iteration 900: error is 1.976311 (50 iterations in 0.03 seconds)

## Iteration 950: error is 1.926869 (50 iterations in 0.03 seconds)

## Iteration 1000: error is 1.835692 (50 iterations in 0.04 seconds)

## Fitting performed in 0.90 seconds.

plot(tsne_out$Y, col=rainbow(2)[sg], pch=16, main='tSNE')

In general, the annotated subpopulations from these tSNE results are not particularly clear-cut.

Still, we may be wondering what genes and pathways characterize these subpopulation? For that, additional analysis is often needed and dimensionality reduction alone does not provide us with such insight.

Pathway and gene set overdispersion analysis (PAGODA)

Additionally, we may be interested in finer, potentially

overlapping/non-binary subpopulations. For example, if we were

clustering apples, PCA might separate red apples from green apples, but

we may be interested in sweet vs. sour apples, or high fiber apples from

low fiber apples. Similarly, in single cells, there may be such

overlapping aspects of heterogeneity that are of biological interest.

PAGODA is a method developed by the Kharchenko lab that enables

identification and characterization of subpopulations in a manner that

resolves these overlapping aspects of transcriptional heterogeneity. For

more information, please refer to the original manuscript by Fan et

al.

PAGODA functions are implemented as part of the scde package.

library(scde)

Each cell is modeled using a mixture of a negative binomial (NB) distribution (for the amplified/detected transcripts) and low-level Poisson distribution (for the unobserved or background-level signal of genes that failed to amplify or were not detected for other reasons). These models can then be used to identify robustly differentially expressed genes.

# EVALUATION NOT NEEDED FOR SAKE OF TIME

knn <- knn.error.models(cd, k = ncol(cd)/4, n.cores = 1, min.count.threshold = 2, min.nonfailed = 5, max.model.plots = 10)

# just load from what we precomputed for you

load('../../data/knn.RData')

head(knn)

PAGODA relies on accurate quantification of excess variance or

overdispersion in genes and gene sets in order to cluster cells and

identify subpopulations. Accurate quantification of this overdispersion

means that we must normalize out expected levels of technical and

intrinsic biological noise. Intuitively, lowly-expressed genes are often

more prone to drop-out and thus may exhibit large variances simply due

to such technical noise.

# EVALUATION NOT NEEDED FOR SAKE OF TIME

varinfo <- pagoda.varnorm(knn, counts = cd, trim = 3/ncol(cd), max.adj.var = 5, n.cores = 1, plot = TRUE)

# normalize out library size as well

varinfo <- pagoda.subtract.aspect(varinfo, colSums(cd[, rownames(knn)]>0))

# just load from what we precomputed for you

load('../../data/varinfo.RData')

names(varinfo)

## [1] "mat" "matw" "arv" "modes" "avmodes" "prior" "edf"

## [8] "batch" "trim"

Briefly, mat is the new normalized gene expression matrix, You can use

?pagoda.varnorm to learn more about the varinfo object.

When assessing for overdispersion in gene sets, we can take advantage of

pre-defined pathway gene sets such as GO annotations and look for

pathways that exhibit statistically significant excess of coordinated

variability. Intuitively, if a pathway is differentially perturbed, we

expect all genes within said pathway to be upregulated or downregulated

in the same group of cells. In PAGODA, for each gene set, we test

whether the amount of variance explained by the first principal

component significantly exceed the background expectation.

# load gene sets

load('../../data/go.env.RData')

# look at some gene sets

head(ls(go.env))

## [1] "GO:0000002 mitochondrial genome maintenance"

## [2] "GO:0000012 single strand break repair"

## [3] "GO:0000018 regulation of DNA recombination"

## [4] "GO:0000030 mannosyltransferase activity"

## [5] "GO:0000038 very long-chain fatty acid metabolic process"

## [6] "GO:0000041 transition metal ion transport"

# look at genes in gene set

get("GO:0000002 mitochondrial genome maintenance", go.env)

## [1] "AKT3" "C10orf2" "DNA2" "MEF2A" "MPV17" "PID1" "SLC25A4"

## [8] "TYMP"

# filter out gene sets that are too small or too big

go.env <- list2env(clean.gos(go.env, min.size=10, max.size=100))

# how many pathways

length(go.env)

## [1] 3225

# EVALUATION NOT NEEDED FOR SAKE OF TIME

# pathway overdispersion

pwpca <- pagoda.pathway.wPCA(varinfo, go.env, n.components = 1, n.cores = 1)

Instead of relying on pre-defined pathways, we can also test on ‘de novo’ gene sets whose expression profiles are well-correlated within the given dataset. This is the most necessary and useful when the provided annotated gene sets are poor or incomplete.

# EVALUATION NOT NEEDED FOR SAKE OF TIME

# de novo gene sets

clpca <- pagoda.gene.clusters(varinfo, trim = 7.1/ncol(varinfo$mat), n.clusters = 150, n.cores = 1, plot = FALSE)

Testing these pre-defined pathways and annotated gene sets may take a few minutes so for the sake of time, we will load a pre-computed version.

load('../../data/pwpca.RData')

clpca <- NULL # For the sake of time, set to NULL

Taking into consideration (ideally) both pre-defined pathways and de-novo gene sets, we can see which aspects of heterogeneity are the most overdispersed and base our cell cluster only on the most overdispersed and informative pathways and gene sets.

# get full info on the top aspects

df <- pagoda.top.aspects(pwpca, clpca, z.score = 1.96, return.table = TRUE)

head(df)

## name npc n score

## 78 GO:0000779 condensed chromosome, centromeric region 1 24 4.689757

## 743 GO:0007059 chromosome segregation 1 97 4.632092

## 17 GO:0000087 mitotic M phase 1 198 4.606980

## 77 GO:0000777 condensed chromosome kinetochore 1 20 4.529740

## 746 GO:0007067 mitotic nuclear division 1 189 4.506514

## 47 GO:0000280 nuclear division 1 189 4.506514

## z adj.z sh.z adj.sh.z

## 78 22.64153 22.44831 NA NA

## 743 33.07666 32.90101 NA NA

## 17 40.87730 40.71825 NA NA

## 77 20.85181 20.65224 NA NA

## 746 39.43297 39.28004 NA NA

## 47 39.43297 39.28004 NA NA

tam <- pagoda.top.aspects(pwpca, clpca, z.score = 1.96)

# determine overall cell clustering

hc <- pagoda.cluster.cells(tam, varinfo)

Because many of our annotated pathways and de novo gene sets likely share many genes or exhibit similar patterns of variability, we must reduce such redundancy to come up with a final coherent characterization of subpopulations.

# reduce redundant aspects

tamr <- pagoda.reduce.loading.redundancy(tam, pwpca, clpca)

tamr2 <- pagoda.reduce.redundancy(tamr, plot = FALSE)

# view final result

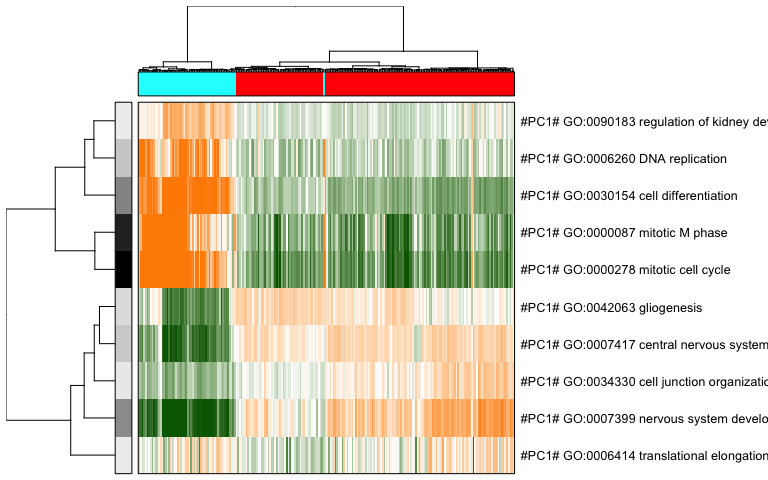

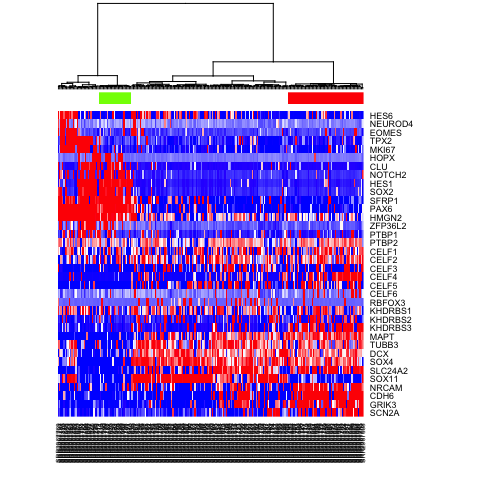

pagoda.view.aspects(tamr2, cell.clustering = hc, box = TRUE, labCol = NA, margins = c(0.5, 20), col.cols = rbind(rainbow(2)[sg]), top=10)

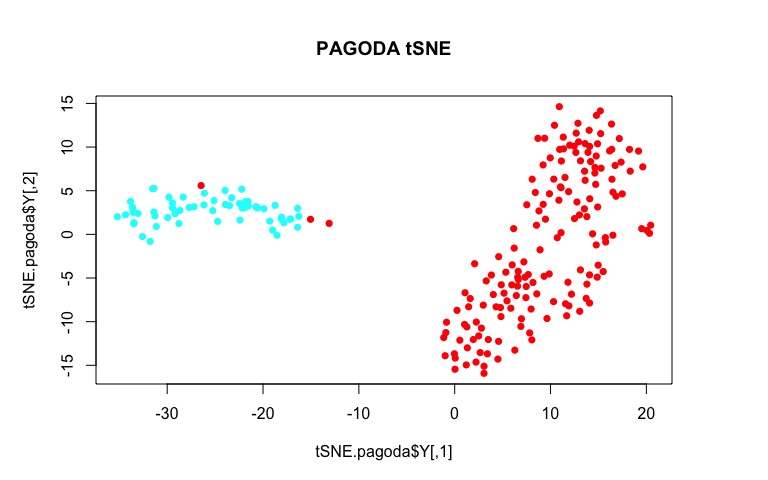

We can also use a 2D embedding of the cells to aid visualization.

library(Rtsne)

# recalculate clustering distance .. we'll need to specify return.details=T

cell.clustering <- pagoda.cluster.cells(tam, varinfo, include.aspects=TRUE, verbose=TRUE, return.details=T)

# fix the seed to ensure reproducible results

set.seed(0)

tSNE.pagoda <- Rtsne(cell.clustering$distance, is_distance=TRUE, perplexity=10)

# plot

par(mfrow=c(1,1), mar = rep(5,4))

plot(tSNE.pagoda$Y, col=rainbow(2)[sg], pch=16, main='PAGODA tSNE')

By using variance normalization and incorporating pathway-level information, our tSNE plot much more cleanly separates the two annotated subpopulations!

We can also create an app to further interactively browse the results. A pre-compiled app has been launched for you here: http:/pklab.med.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/R/rook/scw.xiaochang/index.html.

# compile a browsable app

app <- make.pagoda.app(tamr2, tam, varinfo, go.env, pwpca, clpca, col.cols = rbind(sg), cell.clustering = hc, title = "Camp", embedding = tSNE.pagoda$Y)

# show app in the browser (port 1468)

show.app(app, "Camp", browse = TRUE, port = 1468)

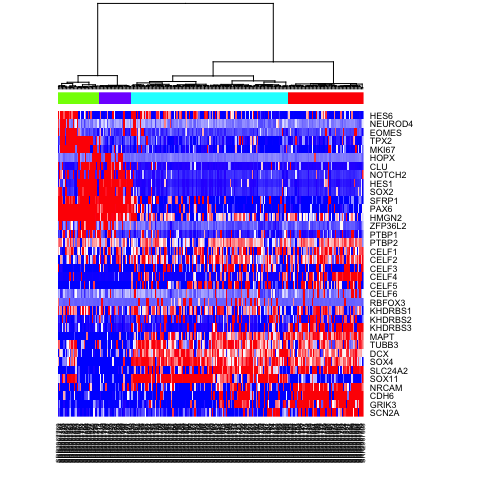

Based on these PAGODA results, we can see pathways and biological

processes driving the main division, which is consistent with previous

annotations of neurons vs NPCs, but we can also see further

heterogeneity not visible by PCA or tSNE alone. In this case, prior

knowledge with known marker genes

can allow us to better interpret these

identified subpopulations as IPCs, RGs, Immature Neurons, and Mature

Neurons.

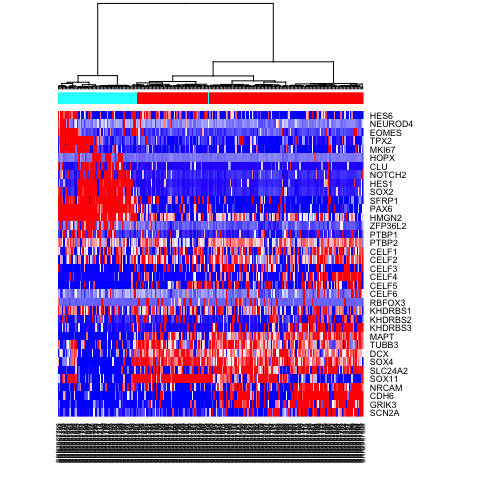

# visualize a few known markers

markers <- c(

"SCN2A","GRIK3","CDH6","NRCAM","SOX11",

"SLC24A2", "SOX4", "DCX", "TUBB3","MAPT",

"KHDRBS3", "KHDRBS2", "KHDRBS1", "RBFOX3",

"CELF6", "CELF5", "CELF4", "CELF3", "CELF2", "CELF1",

"PTBP2", "PTBP1", "ZFP36L2",

"HMGN2", "PAX6", "SFRP1",

"SOX2", "HES1", "NOTCH2", "CLU","HOPX",

"MKI67","TPX2",

"EOMES", "NEUROD4","HES6"

)

# heatmap for subset of gene markers

mat.sub <- varinfo$mat[markers,]

mat.sub[mat.sub < -1] <- -1

mat.sub[mat.sub > 1] <- 1

heatmap(mat.sub[,hc$labels], Colv=as.dendrogram(hc), Rowv=NA, scale="none", col=colorRampPalette(c("blue", "white", "red"))(100), ColSideColors=rainbow(2)[sg])

# Alternatively, define more refined subpopulations

sg2 <- as.factor(cutree(hc, k=4))

names(sg2) <- hc$labels

heatmap(mat.sub[,hc$labels], Colv=as.dendrogram(hc), Rowv=NA, scale="none", col=colorRampPalette(c("blue", "white", "red"))(100), ColSideColors=rainbow(4)[sg2])

Differential expression analysis with scde

To further characterize identified subpopulations, we can identify

differentially expressed genes between the two groups of single cells

using scde. For more information, please refer to the original

manuscript by Kharchenko et

al.

First, let’s pick which identified subpopulations we want to compare using differential expression analysis.

test <- as.character(sg2)

test[test==2] <- NA; test[test==3] <- NA

test <- as.factor(test)

names(test) <- names(sg2)

heatmap(mat.sub[,hc$labels], Colv=as.dendrogram(hc), Rowv=NA, scale="none", col=colorRampPalette(c("blue", "white", "red"))(100), ColSideColors=rainbow(4)[test])

Now, let’s use scde to identify differentially expressed genes.

# scde relies on the same error models

load('../../data/cd.RData')

load('../../data/knn.RData')

# estimate gene expression prior

prior <- scde.expression.prior(models = knn, counts = cd, length.out = 400, show.plot = FALSE)

# run differential expression tests on a subset of genes (to save time)

vi <- c("BCL11B", "CDH6", "CNTNAP2", "GRIK3", "NEUROD6", "RTN1", "RUNX1T1", "SERINC5", "SLC24A2", "STMN2", "AIF1L", "ANP32E", "ARID3C", "ASPM", "ATP1A2", "AURKB", "AXL", "BCAN", "BDH2", "C12orf48")

ediff <- scde.expression.difference(knn, cd[vi,], prior, groups = test, n.cores = 1, verbose = 1)

## comparing groups:

##

## 1 4

## 55 24

## calculating difference posterior

## summarizing differences

# top upregulated genes (tail would show top downregulated ones)

head(ediff[order(abs(ediff$Z), decreasing = TRUE), ])

## lb mle ub ce Z cZ

## STMN2 2.303137 3.207941 7.320687 2.303137 7.160408 6.827743

## CDH6 7.567451 10.076226 10.569755 7.567451 7.150820 6.827743

## CNTNAP2 2.385392 3.331324 8.472255 2.385392 7.048047 6.779055

## BCAN -9.171422 -8.307745 -4.236128 -4.236128 -6.820435 -6.585346

## RUNX1T1 1.932990 2.673284 7.896471 1.932990 6.749579 6.545467

## ATP1A2 -10.117353 -9.294804 -7.649706 -7.649706 -6.580727 -6.399339

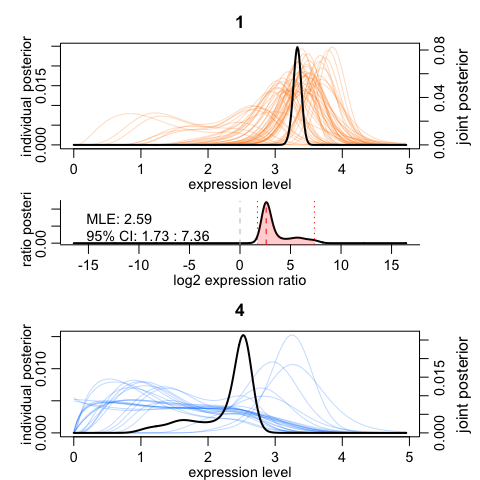

We can visualize the results for one gene. The top and the bottom plots show expression posteriors derived from individual cells (colored lines) and joint posteriors (black lines). The middle plot shows posterior of the expression fold difference between the two cell groups, highlighting the 95% credible interval by the red shading.

# visualize results for one gene

scde.test.gene.expression.difference("NEUROD6", knn, cd, prior, groups = test)

## lb mle ub ce Z cZ

## NEUROD6 1.727353 2.59103 7.361814 1.727353 5.06557 5.06557

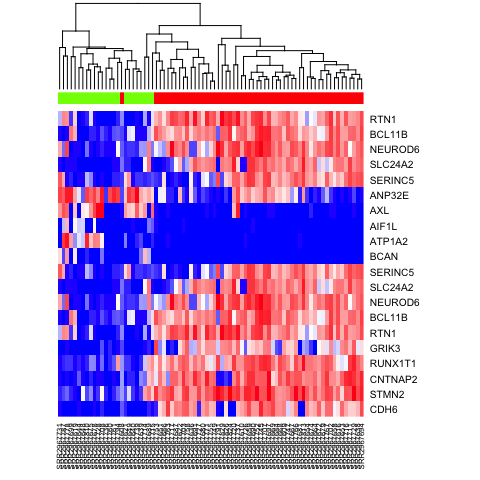

We can also cluster our cells by just the top 10 most differentially upregulated genes in each subpopulation and visualize results with a heatmap.

# heatmap

ediff.sig <- ediff[abs(ediff$cZ) > 1.96, ]

ediff.sig.up <- rownames(ediff.sig[order(ediff.sig$cZ, decreasing = TRUE), ])[1:10]

ediff.sig.down <- rownames(ediff.sig[order(ediff.sig$cZ, decreasing = FALSE), ])[1:10]

heatmap(mat[c(ediff.sig.up, ediff.sig.down), names(na.omit(test))], Rowv=NA, ColSideColors = rainbow(4)[test[names(na.omit(test))]], col=colorRampPalette(c('blue', 'white', 'red'))(100), scale="none")

Once we have a set of differentially expressed genes, we may use techniques such as gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to determine which pathways are differentially up or down regulated. GSEA is not specific to single cell methods and not included in this session but users are encouraged to check out this light-weight R implementation with tutorials on their own time.

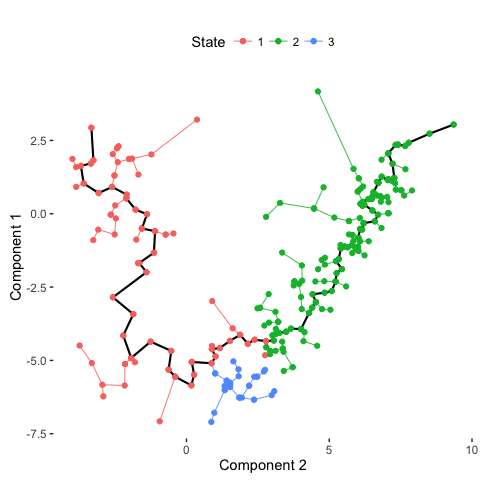

Pseudo-time trajectory analysis with monocle

Cells may not always fall into distinct subpopulations. Rather, they may

form a continuous gradient along a pseudo-time trajectory. To order

cells along their pseudo-time trajectory, we will use monocle from the

Trapnell

lab.

library(monocle)

# monocle takes as input fpkms

load('../../data/fpm.RData')

expression.data <- fpm

# create pheno data object

pheno.data.df <- data.frame(type=sg[colnames(fpm)], pagoda=sg2[colnames(fpm)])

pd <- new('AnnotatedDataFrame', data = pheno.data.df)

# convert data object needed for monocle

data <- newCellDataSet(expression.data, phenoData = pd)

Typically, to order cells by progress, we want to reduce the number of genes analyzed. So we can select for a subset of genes that we believe are important in setting said ordering, such as overdispersed genes. In this example, we will simply choose genes based on prior knowledge.

ordering.genes <- markers # Select genes used for ordering

data <- setOrderingFilter(data, ordering.genes) # Set list of genes for ordering

data <- reduceDimension(data, use_irlba = FALSE) # Reduce dimensionality

set.seed(0) # monocle is also stochastic

data <- orderCells(data, num_paths = 2, reverse = FALSE) # Order cells

# Plot trajectory with inferred branches

plot_spanning_tree(data)

# Compare with previous annotations

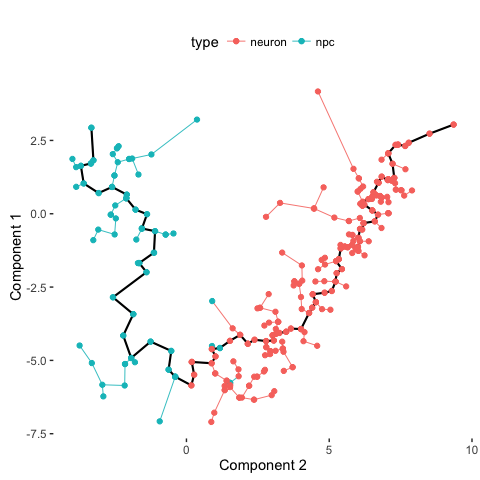

plot_spanning_tree(data, color_by = "type")

# Compare with PAGODA annotations

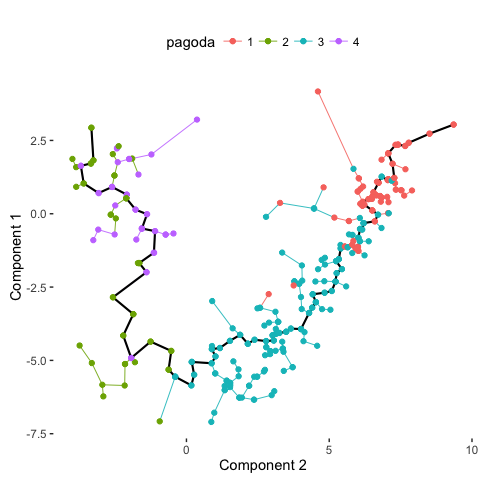

plot_spanning_tree(data, color_by = "pagoda")

Indeed, we can see how neuronal maturation from NPCs to neurons spans a continuum along a single, non-branching trajectory. So do cells fall into distinct subpopulations or are they continuously changing or perhaps both? Just as with human life, age spans a continuum yet we fall into distinct phases of childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and so on, each marked by distinct characteristics. What do you think?

Recent Posts

- Vibe coding with SEraster and STcompare to compare spatial transcriptomics technologies on 22 February 2026

- RNA velocity in situ infers gene expression dynamics using spatial transcriptomics data on 13 October 2025

- Analyzing ICE Arrest Data - Part 2 on 27 September 2025

- Analyzing ICE Detention Data from 2021 to 2025 on 10 July 2025

- Multi-sample Integrative Analysis of Spatial Transcriptomics Data using Sketching and Harmony in Seurat on 22 April 2025